Hacking your brain’s memories isn’t science fiction anymore says Kaspersky Labs

There has been a ton of research about the human brain and how exactly it works with the best minds, pardon the pun, in the business barely scratching the surface of just what that lump of neurons and synapses between our ears can do.

Science fiction theorists and the odd Hollywood filmmaker or two have filled in the gaps with fanciful ideas of how memories and by extent skills can be imparted and transferred to the brain as if it was an organic flash drive.

Remember that scene from the Matrix where Keanu Reeves’ character Neo had a three-inch jack jammed into his brain and he suddenly says, “I know kung fu” ? The premise was that all the combined skills of thousands of years worth of martial arts practice were suddenly transferred, much like a bunch of MP3 files into his brain without him having to actually undergo the traditional physical training required to become an actual martial arts master.

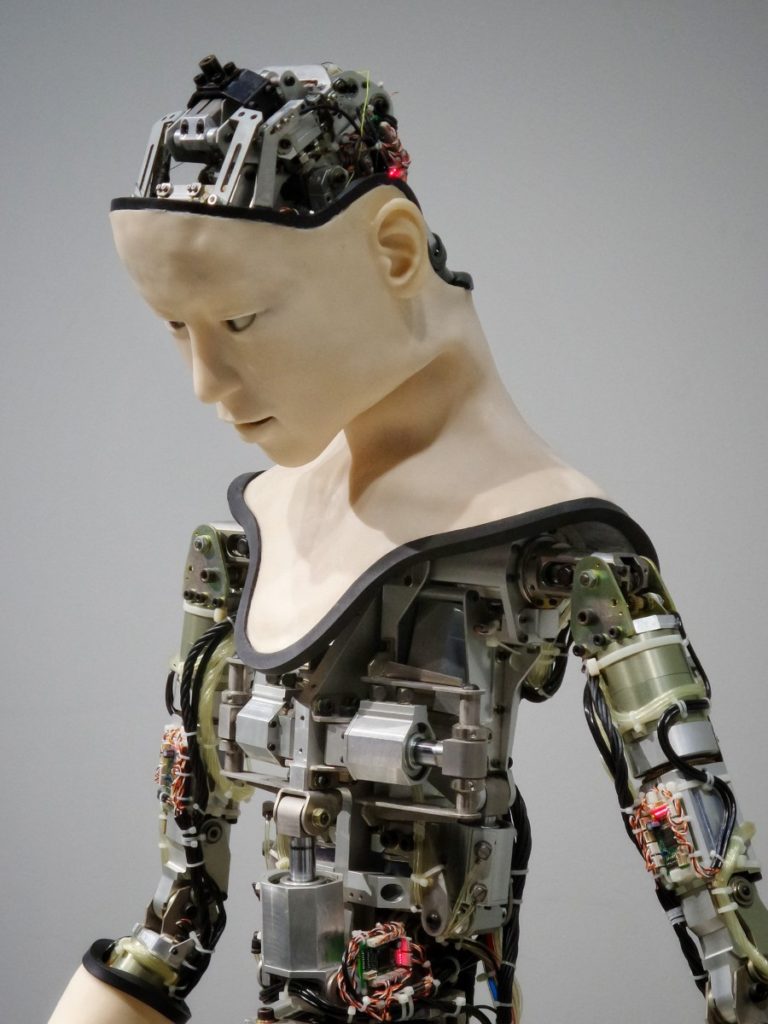

Other science fiction films like Ghost in the Shell theorise that the experiences and tangentially, the skills associated with those experiences like language and whatnot can be transferred between cybernetic bodies, essentially allowing for functional immortality and the digitisation of the soul. In Total Recall, a plain man living in suburbia decides to go on a holiday to Mars without even having to step on the Red Planet by manipulating his memories in commercial grade memory manipulation machines, and – stop me, if you heard of this before – finds out that he is actually a highly trained secret agent who had his memory wiped but which is now miraculously restored – skills and all.

All this sounds like flights of fancy, but according to Kaspersky Labs, the day when we can manipulate memories may not be too far off as the technology to do so exists today.

According to a report by researchers at Kaspersky Lab and the University of Oxford Functional Neurosurgery Group, cyberattackers can possibly exploit and manipulate memory implants to steal, spy on, alter or control human memories. While there are potential benefits – ergo, learning new languages or skills or possibly erasing painful memories – the potential for malicious acts looms on the horizon with the possibility of a Manchurian Candidate scenario or worse, implanting false memories and manipulating them for gain. Passwords aren’t safe anymore when even your own memories are suspect.

Kaspersky Lab teams and the University of Oxford Functional Neurosurgery Group combined practical and theoretical analysis to explore the current potential and vulnerabilities in implanted pulse generations (IPGs) or neurostimulators that are used for deep brain stimulation. Currently, these devices are used to send electrical impulses to specific areas in the brain to treat a number of disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremors, major depression and the like. The latest generation of these IPGs have gone beyond being a mere switch to jolt your noggin and actually have software for clinicians and patients, installed via the usual tablet or smartphone to control them using plain, old mainstream Bluetooth connectivity.

According to the group, they expect scientists to be able to record the brain signals that form memories and then enhance or rewrite them before putting them back into the brain, much like overwriting software within a period of five years. A decade from now, they expect memory boosting implants to be in commercial use and within two decades, it can potentially offer enough control over memories. Don’t like that memory of breaking up with the girl that got away? Zap. Want to suddenly master a new language without spending a year of your life in class? Zap.

New frontiers and new opportunities also mean new areas for malicious cyberattackers to exploit.Dmitry Galov, junior security researcher, Global Research and Analysis Team, Kaspersky Lab said, “Current vulnerabilities matter because the technology that exists today is the foundation for what will exist in the future. Although no attacks targeting neurostimulators have been observed in the wild, points of weakness exist that will not be hard to exploit. We need to bring together healthcare professionals, the cybersecurity industry and manufacturers to investigate and mitigate all potential vulnerabilities, both the ones we see today and the ones that will emerge in the coming years.” Laurie Pycroft, doctoral researcher in the University of Oxford Functional Neurosurgery Group added: “Memory implants are a real and exciting prospect, offering significant healthcare benefits. The prospect of being able to alter and enhance our memories with electrodes may sound like fiction, but it is based on solid science the foundations of which already exist today. Memory prostheses are only a question of time. Collaborating to understand and address emerging risks and vulnerabilities, and doing so while this technology is still relatively new, will pay off in the future.”

Naturally, consumer tech isn’t substantially hardened against dedicated cyberattacks, more so for technology so new that it represents a new frontier for science. The joint team found a number of existing and potential risk scenarios, all of which represent opportunities for cyberattackers:

- Exposed connected infrastructure – the researchers found one serious vulnerability and several worrying misconfigurations in an online management platform popular with surgical teams that could lead an attacker to sensitive data and treatment procedures.

- Insecure or unencrypted data transfer between the implant, the programming software, and any associated networks could enable malicious tampering of a patient’s or even of whole groups of implants (and patients) connected to the same infrastructure. Manipulation could result in changed settings causing pain, paralysis or the theft of private and confidential personal data.

- Design constraints as patient safety takes precedence over security. For example a medical implant needs to be controlled by physicians in emergency situations, including when a patient is rushed into a hospital far from their home. This precludes use of any password that isn’t widely known among clinicians. Further, it means that by default such implants need to be fitted with a software ‘backdoor’.

- Insecure behavior by medical staff – programmers with patient-critical software were found being left with default passwords, used to browse the internet or with additional apps downloaded onto them.

Fortunately, the most terrifying threats of this new field of science are decades away but the technology already exists in a rudimentary fashion via the aforementioned deep brain stimulation devices. Research is ongoing on how memories are created, where they are stored in the brain and how they can be rewritten or manipulated. In any case, these concerns need to be addressed in the years to come. In the meantime, swing by and read the original report The Memory Market: Preparing for a future where cyber-threats target your past is available for reading on Securelist. For more details on other cybersecurity insights and other breaking news, swing by www.kasperskylab.com