Kaspersky shows how it goes hunting for fantastic (online) beasts and how to find them

Ask the average guy on the street about cybersecurity, cybercrime or any of the recent hacks or malware like the recent WannaCry and Petya virus as well as the ironically named NotPetya virus that have been plaguing everyone like a digital version of the bubonic plague and they will likely conjure up the mental image of a punk in a hoodie hunched over a laptop punching buttons in a mysterious fashion even as Matrix-style script scrolls around in neon green lines on the display.

Now, ask them to imagine what the cybersecurity experts who thwart them look like and odds are they will imagine much the same albeit in more dapper suits and nicer offices if any of the recent post-modern Hollywood movies are anything to go by. Ask any of them how exactly they do go about their job though and you will most likely draw a blank look. One chap I spoke to over coffee gave a profound look while gesturing in a presumably wizardly manner,”They do their tech thing like the Matrix and Mission Impossible movies, right?”

Be as it may, that is as far from reality as it gets from the average routine of a cybersecurity practitioner. While it makes for good cinema, an actual cybersecurity expert enjoys a more bullet-free lifestyle in an office more often than not and their work revolves more on research and analysis.

At Kaspersky’s Paleontology of Cybersecurity conference that was held at INTERPOL World Congress in Singapore, the cybersecurity company shed light as to what goes on in the ongoing war in between malicious online criminals and the cybersecurity professionals that work to protect critical systems and the public from them.

Acting as the thin red line that protects individuals, organisations and critical infrastructure from all manner of malicious malefactors online, cybersecurity experts in both the public and private sector often liken their profession to be more of paleontologists, delving in the digital bones and detritus of online crimes and the dissected remains of malicious virii to find the proverbial monsters stalking the darker parts of the Internet.

“It is really about collecting the little bits of evidence that allow researchers to figure out how hackers got in and prevent them from doing it again. We find monsters. We see the bits and pieces of digital artefacts – these ‘broken bones’ of sorts and attempt to find out who and what they belong to,” said Vitaly Kamluk, the Director of Kaspersky’s Global Research and Analysis (GReAT) team in the Asia Pacific region at the three-day conference.

The Lay of the Land

In a conference for invited guests, Vitaly and a team of panelists who consisted of experts in cybersecurity from a diverse array of organisations shared their insights on the current state of cybersecurity as it existed today and more on their work. What is clear is that cybersecurity isn’t a problem that can’t be swept under the carpet as the work of a bunch of college kids out to make mischief. “In 2010 the Stuxnet virus was unleashed and caused significant damage to Iran’s nuclear programme. On that day, it was shown to the world that cybercrime is not a virtual problem anymore. It can affect and destroy objects in the physical world.” said Vitaly. The fact that cyberwarfare has become sufficiently serious and dangerous enough that nation states have begun establishing their own cyberwarfare programmes is proof that the weapons of the future may not necessarily be at delivered by a plane or a warhead but by the press of a button and a download.

It’s up to men like Vitaly to carefully find out what happened in order to reconstruct the sequence of events that initiated the malware attack, where the attack came from, the means of identifying it and ultimately countering it to prevent it from happening again. This all has to be pieced together from a disparate bunch of unassociated clues much like how a dusty, seemingly random pile of bones found in an archeological dig are pieced together to form a picture of a dinosaur. Like archeology, the pieces are not complete and experts have to extrapolate what a dinosaur or, in this case, what a given piece of malware looks like from a few bits of data and clues.

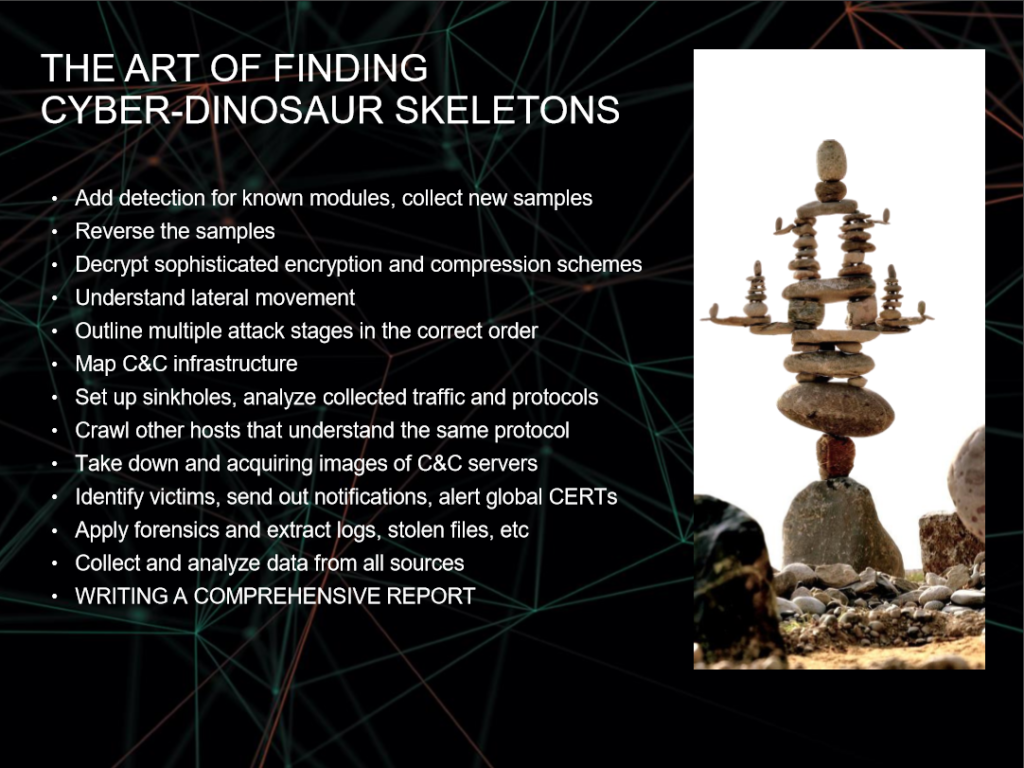

To uncover these ‘cyber dinosaur skeletons’, as Vitaly coins it is an intricate, multi-stage process that requires months of work. The process begins when Vitaly and his team of researchers at Kaspersky’s Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) acquire samples of a virus or investigate the aftermath of an attack. From there – they attempt to dissect the virus, reverse engineering it and seeing what makes it tick. All this may happen even as the threat is ongoing worldwide, which requires nerves of steel seeing as they may be in the hotseat to potentially averting the digital equivalent of the apocalypse.

Investigators attempt to discover specific signatures, patterns, clues or even specific ways of coding or notation within snippets of the virus code that would point it to being related to another existing virus or threat actor (Threat actor is trade speak for bad guy). Ofttimes, it’s a subtle hint such as a virus or malware being coded on a non-English version of Windows that would point it to a particular organisation though other malicious threat actors may deliberately do so just to act as a false flag operation.

GReAT also alerts Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTS) elsewhere around the globe to the threat. From there, they attempt to understand the pathology of a virus or cyberattack so as to prepare a report for dissemination to the public while finding methods to counter the infection. While malware is part and parcel of being a digital citizen these days along with an increasing amount of security consciousness about it due to rigorous awareness programmes, there is one particular avenue that hackers can take advantage of to spread malware like wildfire and cause unprecedented damage – zero day exploits.

Divided by Zero

A good deal of malware preys on human greed or error to get into a system though a select few exploit something else entirely from which there is no defence: zero day exploits. Often unintended programming faults in software, these zero day exploits allow hackers to infiltrate or manipulate software to a terrifying degree to gain administrator privileges.”If this happens, hackers effectively gain the keys to the kingdom.” says Vitaly.

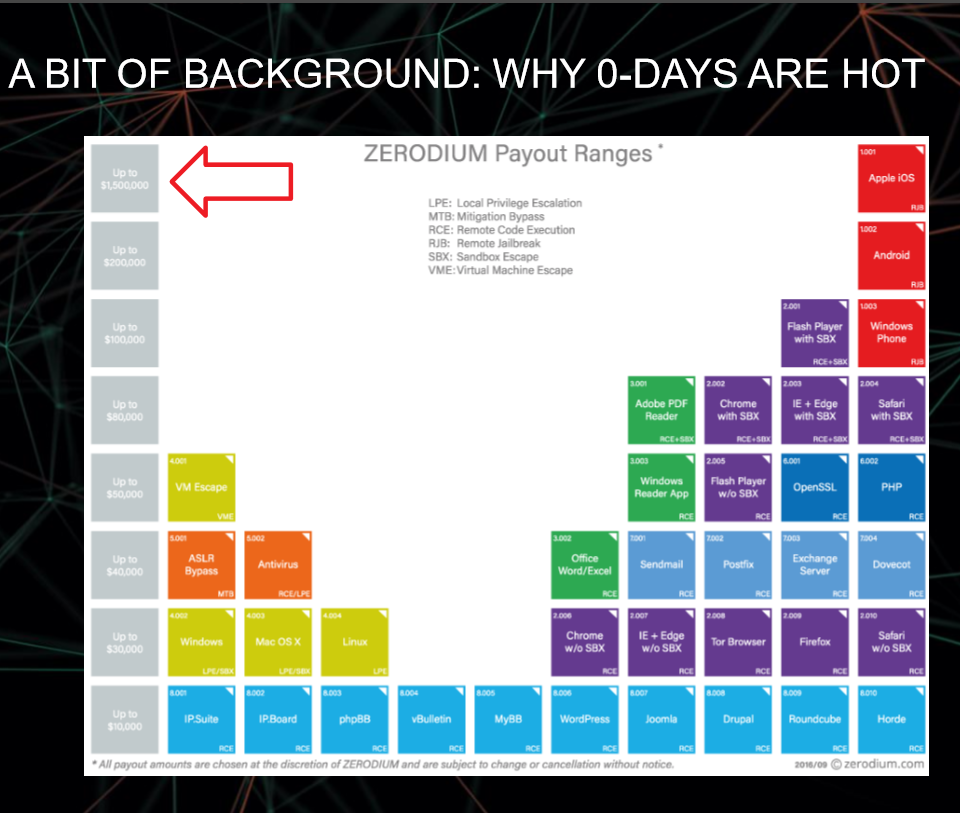

Some organisations both legal and not even keep a ready stockpile of such zero day exploits in reserve while others sell them to the highest bidder. According to Vitaly, there’s a thriving black market for such zero day exploits with prices varying depending on the operating system that is being exploited.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”14″]“One of the most expensive zero day exploits that can be purchased on the black market is US$1.5 million to infect an iPhone” Vitaly Kamluk, Director of GReAT, APAC, Kaspersky Lab [/perfectpullquote]

Oddly enough, iOS and Mac exploits are the most expensive of all. “One of the most expensive zero day exploits that can be purchased on the black market is US$1.5 million to infect an iPhone” said Vitaly. On the other end of the spectrum, an exploit for the Firefox or Chrome browser costs a lot less. With a zero day exploit in hand, a hacker can wreak immense amounts of damage. It’s not a matter of if but when it can happen. Fortunately, once an exploit is used and out in the wild, it has a limited shelf life as the flaw can be patched swifty but during that window of time when there is no countermeasure, all hell can break loose.

Monster Hunting

While experts like Vitaly and cybersecurity teams like GReAT have the knowhow, assets and experience to tackle cybersecurity threats and hunt them down, there simply aren’t enough experts to go around stemming the threat, collecting virus or malware samples at infected PCs and the number of attacks grows daily. Vitality and other cybersecurity simply cannot be everywhere at once and authorities are scrambling just to be able to tackle the problem with a lack of manpower, expertise and assets. With every minute wasted, a virus can spread further.

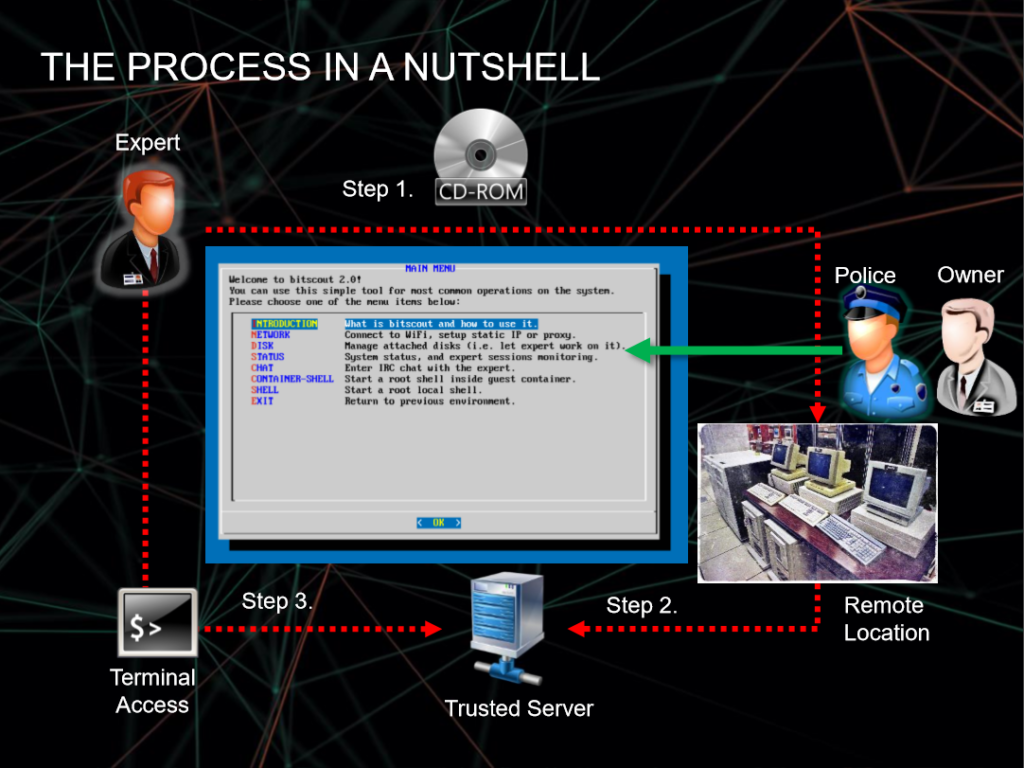

At INTERPOL World 2017, Vitaly revealed the solution – BitScout. Essentially an open source digital forensics tool, BitScout is free for download and can be safely installed on compromised systems via a CD ROM. Once loaded, BitScout helps to collect material critical for a cybersecurity expert to deal with the virus up to and including acquiring a full disk image. BitScout also allows for remote access and assistance to the compromised system, allowing a cybersecurity expert immediate access in a safe and secure fashion without having to be physically present at the location.

“The need to analyze security incidents as efficiently and swiftly as possible is increasingly important, as adversaries grow ever more advanced and stealthy. But speed at all costs is not the answer either – we need to ensure evidence is untainted so that investigations are trusted and results can be qualified for use in court if required. I couldn’t find a tool that allowed us to achieve all of this, freely and easily – so I decided to build one,” said Vitaly Kamluk.

BitScout can be customised and allows other experts to create their own custom forensics tool to suit their unique needs. At present, BitScout has the following features:

-Disk image acquisition even with untrained staff

-Training people on the go (shared view-only terminal session)

-Transferring complex pieces of data to your lab for deeper inspection

-Remote Yara or AV scanning of offline systems (essential against rootkits)

-Search and view registry keys (autoruns, services, plugged USB devices)

-Remote file carving (recovering deleted files)

-Remediation of the remote system if access is authorized by the owner

-Remote scanning of other network nodes (useful for remote incident response)

In the war on cybercrime, BitScout may just offer the most important gift of all – knowledge. If you’re keen to give it a whirl, it can be downloaded for free on GitHub’s code repository here: https://github.com/vitaly-kamluk/bitscout